On the first day of arguments following its summer recess, the Supreme Court announced today they would decline to hear a petition by Domino’s seeking to overturn a lower court’s decision that the pizza delivery giant’s website and mobile app are required to be accessible to the disabled under federal law. The Supreme Court’s decision to pass on the case, one of the first high-profile tests of whether the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) applies as broadly to a business’s online presence as it does to their brick-and-mortar stores, was a win for disability activists who argue that online accessibility is a fundamental right in an era where e-commerce is an increasingly dominant force in the marketplace.

The Domino’s appeal was in response to a lawsuit filed in 2016 by a blind California man named Guillermo Robles, who claimed he was unable to use his screen-reading software to custom order pizzas through the delivery chain’s website or mobile app. Robles’ lawyers argued that this alleged lack of accommodation for the blind and visually impaired violated Title III of the ADA, which “prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in the activities of places of public accommodations.”

The case eventually found its way to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, where a panel of federal judges ruled earlier this year that because Domino’s online ordering system connected customers to the goods and services of a physical retail store the company was required to ensure that its website and app were ADA-compliant.

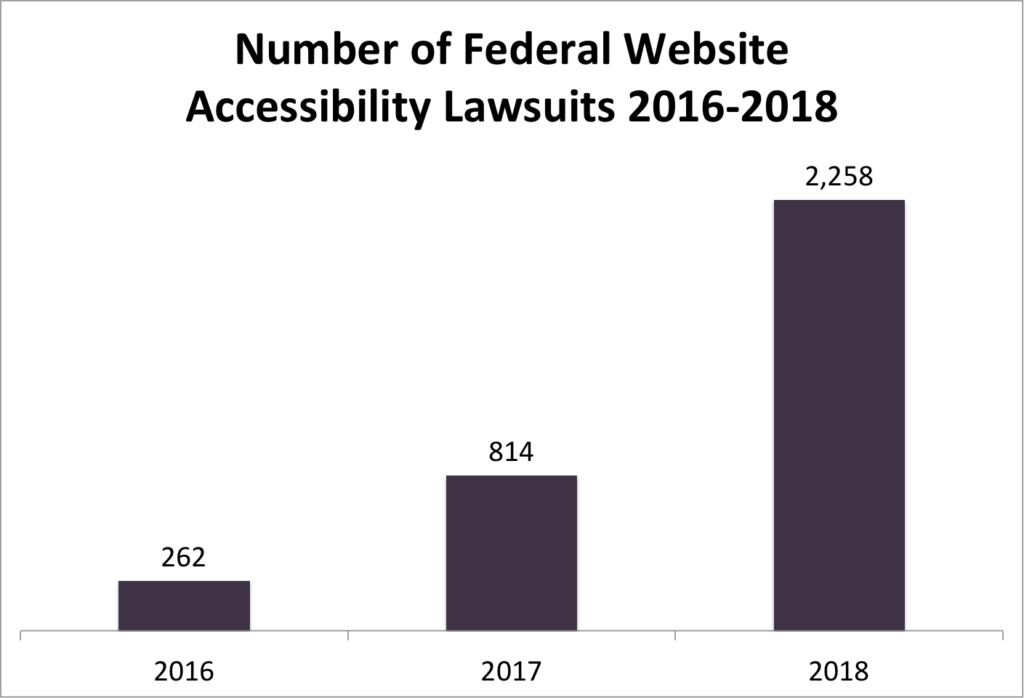

The ADA was written in 1990, just a year after the World Wide Web was invented and long before the rise of smartphones, and the case represents the first of what disability law experts say will be a wave of lawsuits that seek to bring ADA compliance into cyberspace.

In their petition to the Supreme Court, Domino’s lawyers pointed out that the federal government — in particular the U.S. Department of Justice, which is responsible for implementing Title III — has struggled for years to create rules defining online accessibility. Given this lack of guidance, the petition asked how a business like Domino’s could be expected to update their vast, constantly-changing online offerings to accommodate the wide range of disabilities covered under the ADA.

But the Ninth Circuit held that, despite the federal government’s inability to craft uniform national guidance, there were established private industry standards, such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, that the company could follow to make their online offerings ADA-compliant.

Business interests were watching the Domino’s case closely given the potential economic impact of a federal court at some point mandating that all companies doing business online come under compliance.

In an amicus brief filed to the Supreme Court, the U.S Chamber of Commerce argued that allowing the Ninth Circuit’s decision to stand would lead companies to pull their services offline and the net effect would be a less accessible e-commerce environment: “By indicating that each method of access to a company’s goods and services must itself be equally and fully accessible to all individuals, the Ninth Circuit’s decision will discourage companies from pursuing holistic, multi-pronged approaches to providing access to individuals with disabilities.”

The Supreme Court does not give reasons for declining to hear cases, and it may decide to hear the case, or one that raises similar issues, at a later date, but for now Domino’s will have to argue in a lower court that its online services are sufficiently accessible to disabled customers.

In a statement released to the press, the company touted the online accessibility efforts it had already made, continuing: “Although Domino’s is disappointed that the Supreme Court will not review this case, we look forward to presenting our case at the trial court. We also remain steadfast in our belief in the need for federal standards for everyone to follow in making their websites and mobile apps accessible.”

Joseph R. Manning Jr., the lawyer representing Robles, told The Los Angeles Times in an interview that the Supreme Court decision was vindication for the core issue in his client’s lawsuit: “There can be no debate that the blind and visually impaired require accessible websites and mobile apps to function on an equal footing in the modern world.”